Software Engineering with AI: Beyond Vibe-Coding

Since I last wrote about how I use AI for software engineering in 2024, almost everything has changed. Again. Software engineering is forever changed, but, fundamentally still software engineering.

I wrote in late 2024 about how I use AI for Software Engineering. 12-14 months is a lifetime in this tech cycle, and as a consequence, my entire workflow has completely changed. I expect it to change as much in the next 12 months, so this is an ever evolving topic.

If you read this after July 2026 and think “this is stupid!”, it’s quite likely you are right, because things might have changed again. What is clear, is we have come a long way from vibe-coding and autocomplete on steroids.

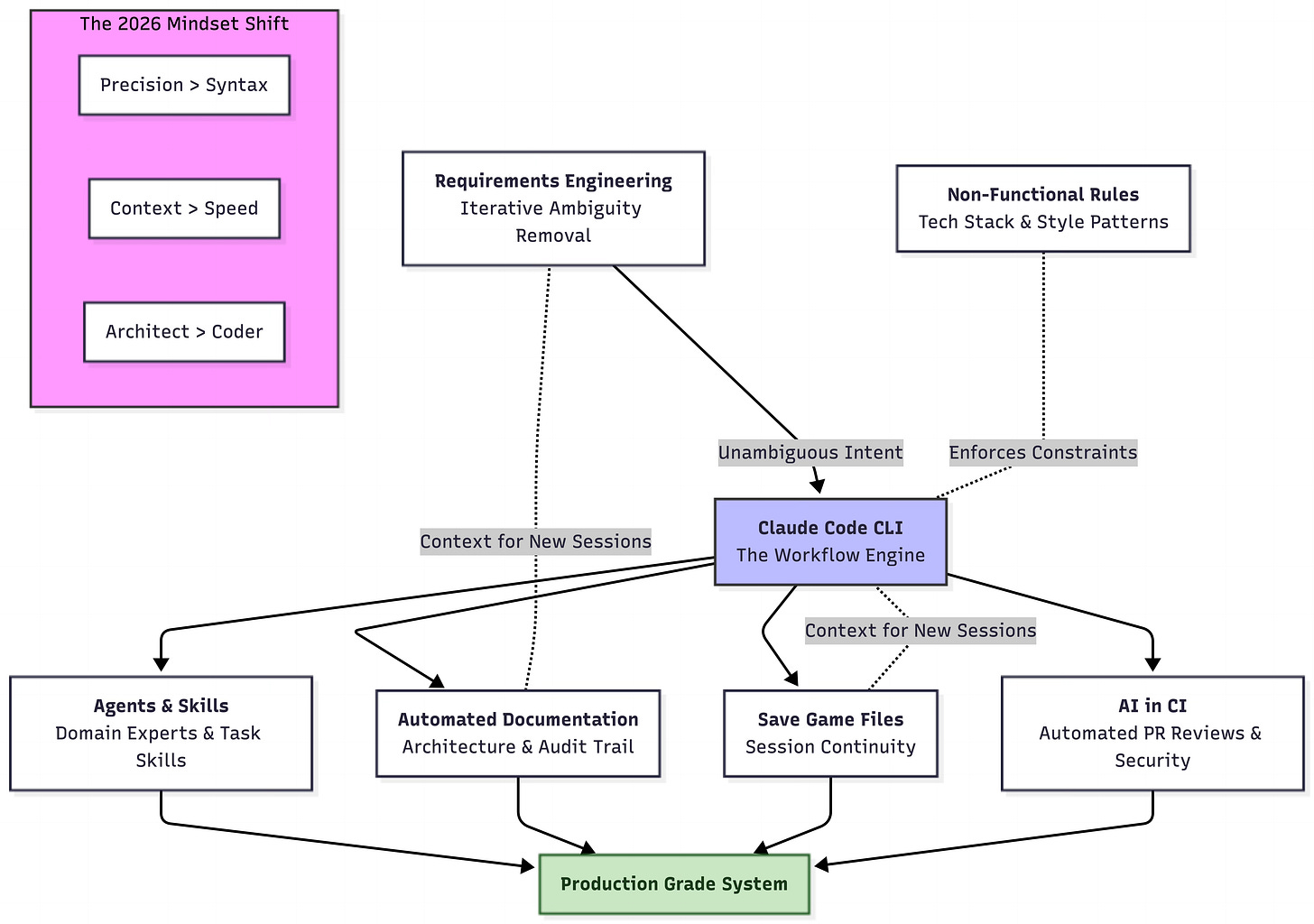

The Seven Pillars

There are seven pillars to my current workflow. We will go into the detail of each below, and I will start from what is likely familiar to people, and move our way towards perhaps less mainstream, but hyper-effective approaches.

The Tooling: Claude Code

My weapon of Choice since spring of 2025 is Claude Code. At first, I was skeptical of the CLI based approach over the IDE-integrated approach, but as I got used to it, I quickly realized it is superior to the alternatives:

We can use whatever editor we want to view code.

The CLI can go off and use whatever tools it needs to do its work.

We can integrate the CLI tool into CI pipelines and other automated workflows.

Freeing our AI assistant from the confines of a desktop application really opens up possibilities.

What is my take on other tools? Github Copilot has come a long way. It’s probably 3-6 months behind Claude, and if your organization is on Copilot, there is no pressing need to switch, but do know you are somewhat behind of being able to do the most powerful use-cases.

Agents & Skills

Let’s first set the scene, with what each means in layman terms: an agent can be seen as an independent process, with its own context (thus not using the size of the main context), that communicates with the main context, but executes tasks and responsibilities that it is assigned as appropriate.

“Skills” I view effectively as reusable prompts for repetitive and/or frequently used tasks. If you view skills in this light, you’ll quickly figure out exactly what skills you need for your specific project: things you need to do frequently and consistently.

What Agents should I have?

Some people go nuts with agents: they’ll have a frontend agent, backend agent, architect agent, unit-test agent and so on. I actually do not buy into this approach: if you consider how humans build cohesive systems, it is not by splitting responsibility across every technical silo possible - this is in fact a means of creating disjointed, poorly architected systems. I find it better to put these responsibilities into the overall Claude instructions: such as “all code should have adequate unit-test coverage, covering both happy- and negative path cases”.

Where I do find agents come in handy, is as domain-experts and executors of ancillary tasks. Some examples:

Documentation Agent: responsible for continuously updating documentation, if relevant, as code changes.

Business Domain Expert Agent: reviews requirements and code, such that they actually make sense in the context of the system and domain you are building.

Code Review & Rule Expert Agent: Solely passive agent that calls out when we duplicate code, write tests that are written to pass, rather than test functionality, violate architectural rules etc.

Requirements Reconciliation Agent: An agent that keeps track of your new work and compares it to past requirements, such that any logical conflicts between new and old requirements can be called out and reconciled.

Security Agent: reviews code for security vulnerabilities.

Requirements Engineering

One fallacy of the AI era is that software engineering is going away. It is not. The level of abstraction is just being raised, same as when we went from punch cards to in-computer code, from manual memory management to garbage collection, and from procedural code to object-oriented and/or functional programming.

In the age of AI, the bulk of engineering will happen at the level of refining requirements to a size and specificity that is appropriate for AI. AI works exceedingly well for solving well-defined, unambiguous problems. It still falls apart if a problem is ambiguous, or there are edges which are ambiguous. If you look at most of what is put into JIRA and similar tools, or into product description documents by non-technical product managers, business analysts and users, you’ll find that the level of ambiguity and lack of specificity will make AI generated solutions mostly fall apart at any scale beyond a single requirement.

So in early 2026, what is the ideal loop for requirements?

This is how I go about it:

Write out a requirement in Markdown, as specific as possible.

Ask Claude to call out ambiguity in the requirement and ask any questions required to make it unambiguous.

Refine collaboratively until Claude is happy.

Reset the context window, go back to 2). Repeat until such time Claude, with a clean context, considers the requirement entirely unambiguous and clear to implement.

If the requirement is larger than what would be a simple task for a human, ask Claude to break it down into sub-tasks.

Again, repeat until you are confident of the specificity and clarity of each step.

Start implementation.

The intent of this loop is to effectively have a plain-language, unambiguous and very clear idea of what is being built, what the edge-cases are and how they will be dealt with, how it fits into the greater context of the system, and how it can be broken down into smaller tasks, if necessary.

It is also useful to keep requirements and tasks broken down, in a structured folder and Markdown format, such that a historical record of requirements and decisions can be accessible both for you as the engineer, and for the AI, to later find and explain why certain things work the way they do, and call out potential conflicting requirements, and how to resolve them, in the future.

But this alone is not enough, this is why we must continuously do the following steps as well:

Non-functional Requirements & Rules

We should create unambiguous documentation for our AI assistant of all non-functional rules and requirements that we should adhere to. This should include things such as:

Our tech-stack.

Rules around testing.

Preferred patterns and code style: do’s and don’t’s.

Levels of linting.

Verification steps before considering a task done (run tests, lints etc).

..anything else that is not technically a requirement, but considered a non-negotiable rule.

If you are only setting up a new project, I’d suggest you again, use your AI assistant to collaboratively build out this requirements- and rule-set, as you discuss potential architectural choices and tech stacks.

Automated Documentation

For your AI assistant to easily understand the system that is built when starting a new session, and also for humans who come onboard, automated documentation is essential.

In the old world, documentation was frequently stale as soon as you’d done the first commit of a README.md, however, as I mentioned in the Agents & Skills-section, with a dedicated documentation agent, documentation does never need to be outdated.

If you start automating documentation from the start, this would be the ideal case, but you can also bootstrap documentation after the fact on existing systems through a process of Socratic questioning, and focusing on infrastructural files as entry points for your AI to start exploring (think Dockerfiles, K8S manifests, build files etc).

What you would hope to produce is:

An entry point README.md for your documentation.

Comprehensive documentation, both in the form of Markdown, and Mermaid diagrams embedded in the markdown, this should contain:

Architectural documentation.

Overall purpose of the system.

Technical principles and rules (your non-functional requirements and rules from before).

Architectural Design Records that explain technical decisions that have been made thus far, when they are of architectural significance.

Your requirements log.

Doing this, and automating it has several key benefits:

Your AI will never get lost in what the system is about, and neither will you.

You will have a comprehensive audit-trail of how the system has evolved, and why.

New conflicting requirements can be reconciled against old requirements, to find a way forward, without breaking the intent of old requirements.

One point of note though, to not drown in documentation, it is worth also instructing the documentation agent in its definition, to not be shy about removing documentation that is out of date.

“Save Game files”: the Secret for Continuity

One pattern I frequently follow when doing larger changes that may span several days (yes, this still happens even in the age of AI), is that I request my assistant to keep a running log of what it has done so far, what is left to do, and what it has learned around solving non-trivial problems in the process. This is so that when I continue in a new session the next day, I won’t have to remember the details myself, nor reteach or retrace past steps with my assistant.

If you’re just vibe-coding a simple webapp with two features, this may seem superfluous, but on any system of sufficient size and complexity, eventually you will come in contact with changes that are non-trivial to complete in a single day.

AI in CI

Reading everything we’ve gone through so far might leave you thinking “couldn’t we further automate some of these steps?”.

And you’d be absolutely right! When it comes to how far we can go in embedding AI in our CI pipelines, only our imagination is the limit, if we use CLI-based tooling.

The obvious steps are:

PR reviews, based on our rules and documentation.

Automated documentation updates.

Security reviews.

..and much, much more.

Key Takeaways for the 2026 Software Engineer

Precision is the new Syntax: Your ability to eliminate ambiguity in requirements is now more important than your ability to remember library APIs.

Context is King: The difference between a “vibe-coded” mess and a production-grade system is the quality of the non-functional rules and documentation you provide your agents.

The CLI is the Workflow Engine: Moving away from the IDE-integrated “chat box” toward CLI-based tools like Claude Code allows for the automation and pipeline integration that professional systems require.

Continuity over Speed: Using “Save Game” files and automated ADRs (Architectural Design Records) ensures that the speed of AI doesn’t lead to a technical debt trap.

Conclusion: The Rise of the Logic Architect

We are witnessing a fundamental shift in the “unit of work” for a software engineer. We used to measure ourselves by the code we wrote - today, we measure it in the clarity of our mental models and the robustness of our agentic workflows.

If you feel like you’re spending more time writing Markdown than JavaScript, don’t worry, you’re doing it right. You are no longer just a coder; you are a Logic Architect. Your job is to build the constraints, the rules, and the context that allow AI to execute with 100% precision.

The “seven pillars” I’ve outlined here aren’t just about being faster - they are about being more intentional. In a world where AI can generate a thousand lines of code in seconds, the human engineer’s most valuable contribution is ensuring that every single one of those lines actually belong there.

See you in 12 months for the next update, unless the agents haven’t rewritten this blog for me by then.